12.27: Choosing a Length

Your Hosts: Brandon, Mary, Dan, and Howard.

We discuss the ways in which we decide upon the length of the stories we write, and at which point(s) in the creative process we make that decision.

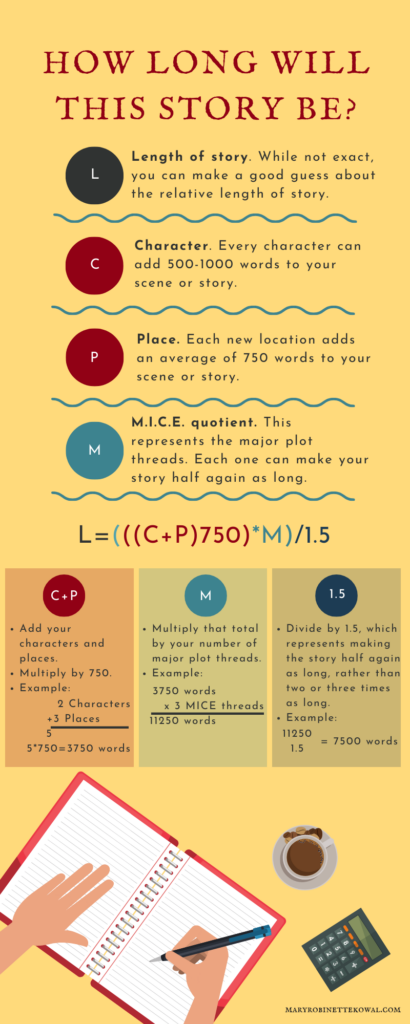

Liner Notes: This is the story-length formula that Mary shared with us:

Ls=((C+L) *750)*M/1.5

(In English: Add the number of characters and the number of locations. Multiply that sum by 750. Then multiply that number by the number of MICE elements the story incorporates and divide by 1.5.)

Or, here’s a handy infographic that she developed later.

Homework: Take a big, complex story, and re-tell it as a children’s story—something you’d read at bedtime, like Are You My Mother? or Goodnight Moon.

Thing of the week: Seventy Maxims of Maximally Effective Mercenaries, by Howard Tayler

(Note: the book is shipping now to Kickstarter backers. You can order it now via Backerkit, but it won’t appear at Amazon or the Schlock Mercenary store until August).

Powered by RedCircle

Transcript

Key Points: Flash Fiction: under 1000 words. Short Story: up to 7,500 words. Novelette: 7,500 to 17,000 words. Novella: up to 40,000 words. Novel: 40,000 and up. How do you know if the story in your head is a novel or a short story? Which do you want to tell? What reader experience do you want — a short punch to the emotional gut, or a longer immersion in a warm tub? The Olympics or a YouTube snippet? Why do you choose one or the other? Who are you trying to sell to? What do you want to do with it? When you write a short story, often deciding that you want it to be short comes first. Which influences structure, decisions to constrain rather than expand. Dénouement, reflecting on the experience, works in novels, but often is too much tacked on for a short story. Have you ever been wrong about the length of a story you were writing? Flash fiction that became a novel! The short story that became a quest. Schlock Mercenary!

The formula! Write a thumbnail sketch. How many characters, how many plot threads, how many locations do you have? Roughly LS = ((C + L) * 750) * (PT * 1.5). Number of characters plus number of locations times 750 words, multiplied by number of plot threads times 1.5. In other words, each character and each location adds about 750 words. Each plot thread multiplies the whole thing by about 1.5. Note: Your writing word count may vary.

[Mary] Season 12, Episode 27.

[Brandon] This is Writing Excuses, Choosing a Length.

[Mary] 15 minutes long.

[Dan] Because you’re in a hurry.

[Howard] And we picked 15 minutes long.

[Brandon] We did. I’m Brandon.

[Mary] I’m Mary.

[Dan] I’m Dan.

[Howard] I’m Howard.

[Brandon] She didn’t pick 15 minutes. We did.

[Dan] She was forced into it. Yes.

[Mary] I was forced into it.

[Howard] And then we picked Mary.

[Mary] I picked the length of my name for this. I’m just Mary here, instead of Mary Robinette.

[Brandon] So. Choosing the right length for your story. Mary, I’m going to pitch at you. Can you tell us the different story lengths?

[Mary] Yes. Okay. So, there are a couple of different definitions, but the ones that most of the people use are that up to 7500 words, you are a short story.

[Brandon] Yep. Arbitrary number, but there’s gotta be one.

[Mary] Yep. Above that, then we go to 1250… Is that right? 1500. Crap.

[Brandon] It depends on who you’re talking to. Because 17,000 is Writers of the Future.

[Dan] 17 is what I’ve heard all the time.

[Mary] Ooo.

[Brandon] Yeah. So that cut off generally is where people go, because Writers of the Future will take 17,000 and under, but not over 17,000. But… Yeah.

[Mary] Oh, interesting. This is why we get…

[Brandon] But that weird one in the middle is the novelette.

[Howard] That’s usually between 7500 and 17,5. That’s typical.

[Brandon] Yes.

[Mary] Above that, we have novella, up to 40,000 words. Which is what Brandon writes.

[Brandon] Occasionally, yes. That’s my short fiction.

[Howard] Also his chapters.

[Brandon] Yeah. I do have plenty of chapters.

[Mary] Then, at the other end of the spectrum, we have things that are under a thousand words are flash fiction. Then you have micro fiction. You have twitter fiction.

[Brandon] And we have a novel going from 40 all the way up…

[Mary] How long’s the one you’re working on now?

[Brandon] 510,000 words is the current word count of Oathbringer.

[Chuckles]

[Dan] Which is literally stretching the bounds of publishability in physical form.

[Brandon] It is pushing… Although Alan Moore did one at 600,000 last year. So, I’m okay.

[Chuckles]

[Brandon] As long as I don’t go as long as Alan Moore, the wonderful crazy wizard of England, then we’re okay.

[Mary] That one book is literally longer than my entire series.

[Laughter]

[Dan] Well, if we want to expand our categorization system here, we have novel, really long novel, I guess, but then series is also something to consider when you’re planning how long a project is going to be.

[Brandon] I agree with that. Which is definitely something that we plan for, but right now, we’re really talking about you’ve got a story in your head. How do you decide how long it should be? I get this question all the time. How do I know if it’s a novel or a short story?

[Mary] Which one do you want to tell? I’m totally serious about this. Because I can take any story idea you give me, and I can make a novel out of it, or I can make a short story out of it. Now it’s going to change. It will definitely change, the reading experience is not going to be the same. But what do you want your reader experience to be, and what do you want your own experience to be writing it? I’ve used this analogy before, but the difference between a novel and a short story is basically the difference between watching the Olympics and watching…

[Brandon] A sport! Yeah. The highlights reel…

[Mary] No, watching a YouTube video.

[Brandon] Okay. Yeah.

[Mary] The YouTube video, you want the swift emotional punch in the gut, you want to begin right as the gymnast goes out to do her flippy flippy, and end right when she sticks the landing.

[Brandon] Or not.

[Mary] Or not.

[Laughter]

[Dan] Depending on which kind of YouTube video.

[Brandon] Exactly.

[Mary] You just want the kitten to be cute. You don’t want to watch them…

[Brandon] Okay. I’m going to push you on this more.

[Dan] Grow up, and become the Savior of the world.

[Brandon] What would lead you individually to choose one or the other for a story you have had in your head?

[Mary] So… It really… At this point in my career, it’s who my trying to sell it to. Unfortunately. Or fortunately.

[Brandon] No, I can talk on that, because I do something similar. Why do I write novellas? The actual answer is I have to get ideas out of my brain and do something different. But I used to do those as novels, and now all the fans ask for sequels to those novels. I’ve entrenched myself in several series… Wouldn’t promise sequels. Whereas when I said, “No. I’m going to step back. I can only spare two weeks. I have to learn this form, so that I can have this thing that I can sell directly to the fans. I can do something different with it.” It wasn’t about the artistic nature of it. It wasn’t the this story is naturally… Which sometimes you feel, but… Really, me learning the novella was pure time issues.

[Mary] I will say that I do actually have a formula for being able to tell where the story is naturally sitting, the story that you’re excited about. So write down what I call a thumbnail sketch, which is basically just a quick… It’s an outline for yourself. It doesn’t need to make sense to anybody else, but what you’re looking at is who are the characters I’m interested in, what are the threads that I’m interested in, and what are the locations that I’m interested in. If you have more than four characters, it’s not a short story. Probably.

[Brandon] When you say characters, you mean characters involved or viewpoint characters?

[Mary] Characters, period.

[Brandon] Characters, period. Okay.

[Mary] I should say that there is a difference between a character in a short story and a character in a… Well. The dividing line of when a character is…

[Dan] Counts as a character?

[Mary] Counts as a character.

[Dan] And not a shield bearer or whatever the… Spear carrier?

[Mary] Spear carrier. It is different, short fiction and novel length. Because in short fiction, basically, if they get a line and a name, they’re a character. What we’re looking at here is basically the proportion of the stage that they’re taking up. In a novel, you can have a name and you can have lines, and you may just be a background character. So, the bellhop. Like, if I have a scene in a coffee shop, and the waitress gets five lines, but the overall story, there’s only 10 lines of dialogue, that waitress is a character. But in a novel, and she’s got five lines, she’s background. So in… What we’re talking about is basically if someone has a name and lines, dialogue… If you are mentioning them in your little thumbnail sketch…

[Brandon] Then you add them into this formula.

[Mary] Right. So the formula goes like this, and we will put this in the liner notes, because I am about to throw math at you. So the length of your story (LS) equals open paren open paren [((]… So the length of your story equals the number of characters plus the number of locations times 750 words. So each character and location takes about 750 words to manage. Then you multiply that times the number of MACE elements… Or thread, plot thread elements. Multiply that by 1.5, because each one has the potential to make your story half again as long. So if you’re sitting there and going, “Oh, I’ve got this great idea for a story, and it’s about these two generals and the conflict that they’re having with their family and then they’re going to be going on this long quest…” You’re like, “Okay. So, long quest, you’ve just mentioned in your thing…”

[Brandon] You’ve added 50% just by adding another plot thread.

[Mary] Yep. Each of them have multiple family members, so we’re looking at six characters each. That’s already… That’s 750 words per character. So you can see immediately that this is going to… Where this is roughly going to land.

[Included from the Liner Notes: This is the story-length formula that Mary shared with us:

Ls=((C+L) *750)*1.5Mq

(In English: Add the number of characters and the number of locations. Multiply that sum by 750. Then multiply that number by 1.5 times the number of MICE elements the story incorporates.)

I would say: LS = ((C+L) * 750) * (1.5 * Mq) ]

[Brandon] Okay.

[Dan] Okay. So I got curious, and I just calculated this out. I… We’re doing a John Cleaver omnibus of the first trilogy, in which I’m including a short story that I just wrote. I punched it into your formula, and it aimed a little higher than my word count, but it was more or less accurate. I’m impressed.

[Mary] It’s… As I say, it’s good for a rough diagnostic. You can totally find things that break this.

[Brandon] Right. It’s just if you’re wondering how long is my story going to be… You could probably play with this for a while. Write some stories, then go back and plug them into it and find your own exact numbers so you can figure it out. Dan, how did you decide short story for this?

[Dan] Well, in this case, it was because I have always wanted to do a bridge between the two John Cleaver trilogies. Tried with Next of Kin, and that’s really not how Next of Kin functions in practice at all. So I gave it another shot, and didn’t want to do a whole novel. So I said, “I’m going to do a short story.” Really, the length of it came down to again, the idea. The concept behind the story is that John is, after the third book ends and before the fourth book starts, just sitting and talking to a therapist, with a twist at the end. That constrained location, there are a couple of extra characters. I knew it couldn’t be much longer than that, because all I really wanted it to be was this conversation, and then we’re done.

[Brandon] I’m seeing… Or just thinking about the fact that a lot of times when you write a short story, length comes first. You say, “I want to submit to X, Y, or Z. I am going to write a short story for it.” Or even, you sit down and say, “I’d like to try a short story.” How does that influence… Like, when I write most of my novel, I go a certain length and just kind of go. Particularly, early in my career. Now I know, kind of in the back of my head, “Oh, it has this many plots and things.” But I would just kind of go. You can’t do that with a short story as easily, because you’re thinking about markets, you’re thinking about where to pitch it. How does that influence how you write one?

[Mary] Well, one of the things that influences for me is the structure. So, aside from just the character… The number of characters and locations… I mean, it starts influencing it immediately, because I will choose to constrain rather than letting things expand. It’s like, “Can I reuse this location, can a character I’ve already introduced serve this purpose, or do I actually need that new character?” So it will affect me there, but the other place it affects me is structure, when I’m thinking about the number of scenes that I have, and where I put those scene breaks. So again, I’m talking about a proportional thing. Like, if you are… If you go to the opera, and you’re watching Aida and it’s a four hour opera with two intermissions, you are happy about those two intermissions. An hour and a half in, you take a 20 minute intermission. Great! If it’s a 45 minute show, and I have an intermission 30 minutes in that’s 20 minutes long, chances are people aren’t coming back.

[Laughter]

[Mary] For those remaining 15 minutes. If they do, there’s no way you can ramp up to that tension level again. That’s a mistake that I see a lot of people make in their short fiction is they’ll have this really long scene. Then, you can see a lot of early career writers do this, the very last scene, they’ll have this short scene tacked on at the end, often from somebody else’s point of view. That’s supposed to be the surprising twist. But there’s not enough space and room for the reader to invest and have that emotional reaction again. So if I want that kind of twist, then I look at how that can be part of the scene. It affects where I’m going to put my scene breaks, so that… A lot of these proportional questions are the same kinds of things that you’re thinking about with a novel, but the flaws become glaringly obvious with a short story.

[Brandon] Right. Well, with a novel, you often want more dénouement. You want to sit back and experience the characters reflecting on just how things just happened. Wow! Short story, you don’t want that. Because it would be so short, it’s just not part of it, it’s… It’ll feel tacked on. So when you shrink everything proportionally, on the short story, a lot of those things just don’t belong anymore.

[Mary] One of the things that you’re doing with the dénouement is that you’re giving the reader space to ease out of an environment that they’ve been immersed in. Whereas with short fiction, the immersion… Granted, you can totally find short stories that give you that sense, but for the most part, just the subjective time that the reader has spent reading it, they aren’t as immersed in it.

[Brandon] Let’s stop for our book of the week, which is… Howard’s book!

[Chorus: Yay!]

[Howard] Schlock Mercenary readers have been asking for 10 years for the 70 Maxims of Maximally Effective Mercenaries. They’ve been wanting this collection of pithy, in-world, unwisdom… Terrible, terrible advice. It is now complete. The 70 Maxims of Maximally Effective Mercenaries is an in-world artifact from the Schlock Mercenary universe. The way the book is designed is so that you will feel like you have picked up anything that is from the universe. There’s two editions. There is the edition that is pristine, as if you bought it off the shelf, and there is the addition that has passed through the hands of Karl Tagon for 30 years, his son Kaff for maybe 10, Capt. Murtaugh and Sgt. Schlock, and all of them have written in it.

[Brandon] You handed these out to us today, and we were all sitting and giggling.

[Dan] Yeah. Just like little kids playing with toys, because it was so fun to page through.

[Howard] I added… The most fun for me about these… Writing the maxims themselves is terribly difficult, because… I mean, you talk about selecting a length. They have to be short. They have to be pithy. It’s so crunchy. The thing that I loved was writing the scholar text underneath…

[Mary] Those are just so much fun.

[Laughter]

[Howard] Where I start being pseudo-erudite about these words that I wrote, and picking apart all of the flaws that I’ve found in my own… Oh, it’s delicious. Anyway, you can find these at Schlock Merc… Or store.schlockmercenary.com. By now, when this podcast airs in July, Amazon may already have copies of these, and if you’re coming to GenCon, we’ll have those there.

[Brandon] And you and me and Dan will be at GenCon.

[Dan] Correct.

[Brandon] I think Mary will be?

[Mary] I have not decided yet. I’m trying to travel less, which is not working out so far.

[Laughter]

[Brandon] Let’s ask another question of the podcasters. Have you ever been wildly wrong about the length of the story you were working on?

[Chorus: Yes.]

[Laughter]

[Mary] Shades of Milk and Honey began as flash fiction.

[Brandon] Ooo. Wow. Okay. I’ve never written one of those.

[Laughter]

[Mary] Yep. This was before I had figured out the whole formula thing. If I had, I would have looked at it and immediately realized I had a problem, because in the first scene, which was the short story, had four characters in it. It was 1000 words long. I’m like, “There’s a problem right there.”

[Laughter]

[Brandon] Dan?

[Dan] Yeah. My Mormon pioneer superhero zombie story, I thought it was going to be a short story. I just could not find a way to wrap it up. It was because of all the extra locations. That’s what kept expanding, is they needed to go on a quest to rescue people, and so it ended up being way longer than intended.

[Brandon] Howard?

[Howard] I really hadn’t been expecting Schlock Mercenary to take 18 years…

[Laughter]

[Howard] To not yet be done. It’s… A better example. There have been several Schlock Mercenary stories where I have run up against the limitations implied by the formula that Mary has provided, and which will be in the liner notes, if hearing somebody say open paren open paren does not immediately communicate the visual…

[Mary] Well, and I didn’t do any of the close parens.

[Chuckles]

[Howard] Yeah, that’s going to make some… Sorry, everybody. Close paren close paren. I know many of you were very uptight about that.

[Laughter]

[Brandon] Wow. All that stuff is in the formula. It’s going to be really difficult…

[Laughter]

[Howard] It’s not going to compile. But at least we closed the parentheses. Many, many times I’ve thought, “Oh, I’m going to tell this little side thing,” and realized, “Oh, I just bloated the story huge.” And I made a promise with this side thing that I now need to resolve later. I’ve gotten better at not doing that, but… [Garbled]

[Brandon] So none of them have been shorter than you’d expect? Which is interesting.

[Mary] Ye… I have had that, too. But you’re right, it doesn’t happen as often.

[Brandon] So you were pointing at me for my example?

[Mary] Yeah.

[Brandon] My best example is the second era Mistborn books. This is very illustrative of how my process is. I sat down to write a short story, and I realized quickly on, I wanted to tell a larger story. I actually trashed the short story. Though I do think I put it up eventually on the Patreon. I trashed the short story, and then wrote a novel instead. My short story did not become a novel. This is very frequently misquoted online. I didn’t sit down and accidentally… Like, I joke, “Oh, I accidentally wrote another novel.” That doesn’t actually happen to me. I can spitball a length, and know now… Sometimes they are longer. Like Oathbringer is at 500,000 right now. When I outlined it, I’m like, “This is going to be 450.” I will probably get to 520 and then cut down to 480. I’ve been telling people 450 for a long time though. So, I mean, that’s an extra 30,000 words. That’s a big extra.

[Howard] But as a percentage…

[Brandon] But when you’re working with a 400,000 word book and things like this…

[Howard] You missed by 9%.

[Brandon] I’m… Usually I tell people I’m usually within 10 to 15% when I shoot at something for a length.

[Dan] I actually do have a story that ended up way shorter than I intended. Which was Next of Kin, which I mentioned earlier. Because that was originally intended to be not a full novel but much longer than it was. I was aiming for around 40 or 50,000 words. I think it’s half that. I don’t remember the exact word count. But I… somewhere along writing in the third or fourth scene, realized, “Wait. I don’t know which story I want to tell.” Which means once I figured that out, oh, then it has to end here, which means it’s going to be much shorter than I thought it was going to be.

[Howard] One of the structural bits that I… It happens to me every week is when I am trying to determine what the Monday through Sunday series of strips, or the Sunday through Saturday series of strips is going to be, and I will often break things up into three strip, or three row, blocks. Where Sunday is a scene. And MondayTuesdayWednesday is a scene. And ThursdayFridaySaturday is a scene. What I found is that when I am wrong about how I’ve plotted things, I will end up with a MondayTuesday that is a scene all by itself, which often feels a little bit too short. So I have to do things to make it work.

[Brandon] Let’s stop here for some homework, which, Howard, you have for us.

[Howard] Absolutely. Now I need to pull up the… Yes. Now I remember what I was going to say. All right. Take a story. Take a big, complex sort of story, and rewrite it as a children’s story. When I say children’s story, I mean a story that you would tell to little kids. A story that would be like a little picture book type story. The “Are you my mother?” kind of story.

[Mary] Terrifying.

[Howard] Take something complex…

[Dan] Good night, [inaudible]

[Howard] Take something terrifying. And retell it as a children’s story.

[Brandon] Excellent. Like, “Good night, Dune.”

[Laughter]

[Brandon] If you’ve never seen that, go look it up.

[Mary] Yes. That’s a great one.

[Brandon] This has been Writing Excuses. You’re out of excuses, now go write.