19.32: An Interview on Character with CL Clark

We sat down with CL Clark to talk about character—specifically, how they build different POV characters in the compressed space of a short story. We dive into plot processing (a tool CL Clark has learned from Mary Robinette!), how to specify the stakes of your world, and how to build distinct characters.

Thing of the Week: Reasons Not To Worry: How to be Stoic in Chaotic Times by Brigid Delaney

Homework: “4 Scenes About Power” — Write four scenes: (1) a scene in which your protagonist does something to someone else, (2) a scene in which someone does something for someone else, (3) a scene in which your protagonist has something done to them, and (4) a scene in which your protagonist does something with someone else.

Liner Notes:

Steering the Craft: A Twenty-First-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story by Ursula K. Le Guin

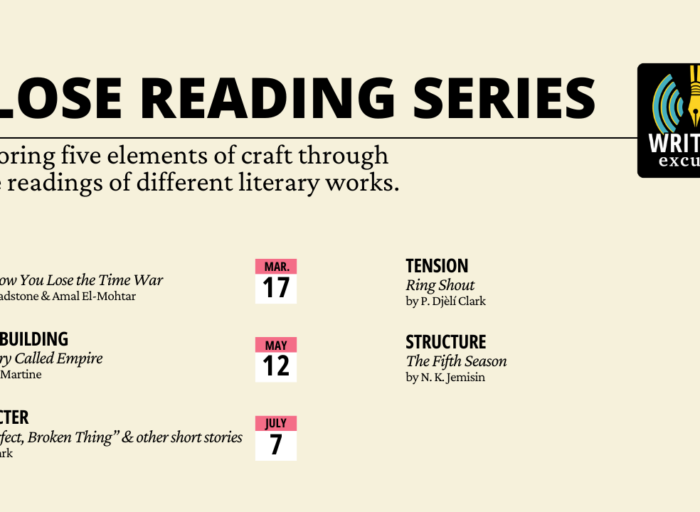

Close Reading Series: Texts & Timeline

Next up is Tension! Starting September 1, we’ll be diving into Ring Shout by P. Djèlí Clark. Please note, this novella uses tools from the horror genre to add tension, and this can be intense for some readers!

Credits: Your hosts for this episode were Mary Robinette Kowal and Erin Roberts. Our guest was CL Clark. It was produced by Emma Reynolds, recorded by Marshall Carr, Jr., and mastered by Alex Jackson.

Join Our Writing Community!

Powered by RedCircle

Transcript

Key points: What do you do when you think “It’s time for me to write a short story and it should have a character?” Triage your characters, who would be there. Then pick a few you are interested in, and ask what they want, and drill down into the stakes. Big stakes or internal stakes? Both! Relationships. Do you approach character differently when you write novel length versus short length? Yes. If they are loadbearing, you need to flesh them out. How do you pick what to include in a short story? Not so much picking out what to put in, but what to take out. Pay attention to what you want to play with.

[Season 19, Episode 32]

[Mary Robinette] This episode of Writing Excuses has been brought to you by our listeners, patrons, and friends. If you would like to learn how to support this podcast, visit www.patreon.com/writingexcuses.

[Howard] You’re invited to the Writing Excuses Cruise, an annual event for writers who want dedicated time to focus on honing their craft, connecting with their peers, and getting away from the grind of daily life. Join the full cast of Writing Excuses as we sail from Los Angeles aboard the Navigator of the Seas from September 19th through 27th in 2024, with stops in Ensenada, Cabo San Lucas, and Mazatlán. The cruise offers seminars, exercises, and group sessions, an ideal blend of relaxation, learning, and writing, all while sailing the Mexican Riviera. For tickets and more information, visit writingexcuses.com/retreats.

[Season 19, Episode 32]

[Mary Robinette] This is Writing Excuses.

[Erin] An Interview on Character with CL Clark.

[Mary Robinette] I’m Mary Robinette.

[Erin] I’m Erin.

[Mary Robinette] And we have a special guest with us today, CL Clark. You’ve been reading their work for a couple of weeks, now we are extremely happy to have them with us.

[CL] Hi, everyone. I’m CL Clark. I am the author of The Unbroken and The Faithless and several short stories. I’m really excited to be here. Yay.

[Mary Robinette] So, the reason that we picked your stories was we wanted to have this conversation about character. There were a couple of things that short stories offered the opportunity to do, which was to look at how you built three different characters, three different POV characters, in a very compressed space. We looked at The Cook, Your Eyes, My Beacon: Being an account of several misadventures and how I found my way home, and You Perfect, Broken Thing. All three of these characters are really distinct. They have different backgrounds, they have different personalities, different wants. What… Like, what are you doing when you’re sitting down and thinking, “Well, it’s time for me to write a short story and I guess it should have a character?”

[CL] Okay. So, I should also say that I have been a really big fan of Writing Excuses from a very, very long time ago.

[Chuckles]

[CL] So, one of the things that I do, not with every story, but for many stories, I actually stole from you, Mary Robinette.

[Mary Robinette] Oh. How convenient.

[Chuckles]

[CL] Very convenient. But I used to be a patreon on your Patreon, and you shared at some point this sort of plot process thing that you did. There’s… At the beginning of that plot processing, you do this sort of… Or you did, I don’t know if you still do it, but I found it really helpful. That you would do this kind of triaging of the characters, and, like, starting with who would be there at this whatever place or situation you’d be in. Pick a few that you’d be interested in in focusing on or that you’re just mostly interested in. Then asking what they want, and drilling down into the stakes. I found that the more you figured out a character’s world and situation, the better… The more distinct they became. The more distinct they became, the more interesting their story was and the more they… I was able to kind of hone in on what made this story different from other stories that I was writing.

[Mary Robinette] I think that that’s… So, first of all, I’m super glad that that worksheet is useful. It is on the podcast website, so folks can grab it. But I also find that, like, knowing what is important to a character is one of the things that really drives this. Part of the reason this is coming to, like, oh, yeah, it’s a really good reminder, is that I just wrote a short story with a character who is a secondary character in the Lady Astronaut novels, and wrote her as a main character, and realized I did not know her at all. It is that, like, what is she afraid of? What does she want? What does happiness look like for her?

[CL] Definitely.

[Erin] I was going to say, I wonder, because I was thinking about, like, what characters want. I think one of the really interesting things in all of these stories is that all of the characters have, like, big wants on the surface, like, big things that they’re dealing with, like, I need to get through this competition, I need to… I’m in the middle of this war. I need to figure out what’s going on with this lighthouse. But I feel like when I think about the characters and what they want, I keep thinking back to their relationships with the other characters. So I’m wondering, like, when you’re coming up with this, are you thinking about those big stakes, are you thinking about, like, their internal, like, what they’re dealing with on the inside, both?

[CL] Both.

[Chuckles]

[CL] Because I like… I really like writing stories about relationships and not always romantic, but often romantic. Just because I think stories are the most interesting for me personally when the thing that is getting in the way is another person. That other person can also be yourself. It’s very often, like, I want this and I also want that, and somehow they’re mutually exclusive. But how somebody navigates around another person, not necessarily just in like a physical, like… Now I’m going to beat this person and kill them and now I have whatever, but, like, negotiating or developing a relationship to get what you want is very interesting to me. So they’re not necessarily distinct when I think of whatever the stakes are. But since that other person is usually one of the three characters that I kind of brainstormed at the beginning, they just sort of come looped together already. If that makes sense. Like, they’re a web that I can start pulling on and tying together.

[Mary Robinette] Yeah, that does make sense. Because there’s that saying, everybody’s the hero of their own story. So if you start thinking about what the stakes are, what the other person’s wants are. One of the things that I particularly love in The Cook is how much that story is really just about the relationship. Like, there’s this massive war that happens offstage that we spent a lot of time talking about how delicious it is to watch both characters change in each scene that they’re in. The relationship to each other inflected by this experience that we don’t participate in. We only participate in their relationship. That’s, I think, one of the things that is really, like, really lovely and beautiful about having given them both something that they want, something that’s driving them.

[Erin] Yeah. I also think it’s interesting because, like, even though, like, the war is such a small part in some ways of the story, it casts such a big shadow. Like, it’s not like you could take that story and be like, it’s not a war anymore, it’s a parade…

[Laughter]

[Erin] And it would be the same story. You know what I mean. It would be a very, very different story. I love that you’re able to…

[Mary Robinette] [garbled thematic story]

[Erin] [garbled] planning or something instruments…

[Garlic yeah]

[Erin] But the amazing thing about the parade version of the Cook is such a different story, because we feel the impact of things that you didn’t even show us. I love that you’re saying that they come to you intertwined, because they feel intertwined. It feels like if you took out a thread from one, it would unravel the thread of the other, even if it isn’t a thread that we see that, like, hugely on the page, like explicitly. So I just love that.

[Mary Robinette] Yeah.

[Erin] Also, please write The Cook at the Thanksgiving Day Parade.

[Mary Robinette] Please. Yeah.

[Laughter]

[CL] Hey, a fanfiction. I do do a fanfiction of my own works.

[Erin] Do you really? Wait, wait, wait. Say more?

[Mary Robinette] We’re going to do…

[CL] I’m sorry. Some of it is not as wholesome, so…

[Mary Robinette] Yep.

[Erin] I know what I’m doing after this. Okay!

[Mary Robinette] Yep. Have the same thoughts. [Garbled] novels, that’s interesting to me. Do you find that you have to approach character differently when you write at novel length than you do when you’re writing at short length?

[CL] Absolutely. 100 percent. But, like, just on the very barest level. Kind of what you said, Mary Robinette, about your side character that you didn’t know at all when you actually started trying to write her story. Some stuff that I can get away with in a short story just doesn’t fly in a novel. Because, for me, I can just feel it when I have to be with a character longer, even if there a side character. If they have any loadbearing at all, and they’re not fleshed out enough, I can just feel it, and every scene with them feels a little flat. Or they… I don’t know, they just don’t feel… I’ve actually been dealing with this recently with characters in a couple of different books. There’s just something about even scenes that they’re not in or other character storylines, like main character storylines, that feel off if someone is supposed to be important but they’re not fleshed out enough to them. So, like… Well, I’ll just say so. In the novel series, in the Unbroken and The Faithless, there is a friend of the princes’s named Sabeen who I love to pieces, but I had to work a lot on her, because she has not ever gotten a point of view chapter or anything like that, but she supposed to be really important to Luca. Enough that Luca make some questionable decisions about her. Or around her. If she’s not, if Sabeen is not a strong enough character to deserve those decisions…

[Mary Robinette] Yeah.

[CL] Then the whole book kind of falls apart. So… Yes. It’s very different that way.

[Mary Robinette] Yeah. I wonder if… As we’re thinking about it, because I do tend to think of them as being in the same general toolbox, I wonder how much of it is audience expectation that in a short story, we know that the author can’t include everything, and so we’re used to filling in the gaps for them, but in the novel, we hunger for that, for those details that are not necessarily there, and we’re with them longer too.

[Erin] I think it’s also that idea of loadbearing. Like, I love that is a concept. Like, you’re not holding up as much stuff. Like, as short story is, like, you’re just holding up an umbrella.

[Mary Robinette] Yeah.

[Erin] And not a house. So the amount that you need to know in order to bear that load, seems like it would be a lot less.

[Mary Robinette] Yeah. I mean…

[Erin] I don’t know if that is true for you, or even how you figure out what it is that you need to know to make the story work, either in short or in novel length.

[CL] I think, like… Definitely one of the things that seems easier in a short story is… Not easier, just for the characters that… Part of the reason, I think, that you can sort of sketch out just is partly reader expectation, but partly it’s easier to work with negative space when, like, so much of a short story and the world building and the plot, all of it, is negative space.

[Mary Robinette] Yeah.

[CL] Whereas with a novel, all of it is… Not all of it, but a much higher percentage of it is fully filled out. Like, main characters in short stories are not the fullest, most fleshed out things always compared to a novel protagonist.

[Mary Robinette] Yeah. Yeah, that’s true. I like the way you’re thinking about it with negative space. That probably appeals to me because I was an art major. For people who haven’t heard this term before, it refers to a concept when you’re looking at a picture. There’s the object that… The subject of the picture. There’s a vase, or a person. Then the negative space is all of the stuff that is around them. That negative space is as much a part of the composition is the figure itself I think it’s a very useful concept in short fiction. The one where you see it the most clearly is The Cook, where so much of the war happens in the negative space. But I think it’s also… It’s also there very much in You Perfect, Broken Thing as well. Just lines like one of my favorite lines in the… I mean, I have a lot of favorite lines. But at the end of the very first thing, you say, “This is not my first race.” That is such a good example of like telling you so much. You’re not describing all of the other races, you’re not doing any of that. But you’re giving us this negative space, and we can pour the rest of ourselves into it. I think it does a really good job of creating space for the reader in this story.

[Erin] I was just thinking about this negative space idea, and, like, what readers expect. Because I was thinking, like, if you leave… It’s basically what you already said, but if you leave negative space in a story, it feels intentional. If you leave negative space in a novel, it often feels like you just forgot. Like you just forgot that part of a page. Like, I just stopped coloring and left. I’m wondering, though, in a short story, how do you know what you do need to fill in? Like, you’ve ordered a cast that’s shadowlike… How do you know that you need to like make a reference even to a first race, which you didn’t have to do at all. I could have been, like, no, I’m just telling you about the current thing. Like, how do you pick those pieces that give you enough of, like, an outline that the negative space comes through in a really clear, cool way?

[CL] That is something that I struggled very hard with when I first started writing short stories. But I do want to just drop in re negative space in novels, I do think that it can work. I just think it’s harder to navigate with a slight… The current sort of expectation in the fantasy genre of a quicker pace kind of reads where things are a little bit more spelled out, but sometimes… I think I have a fair amount of negative space in my novels as well. Just, I don’t necessarily rely on it in the same way as I do in short fiction. For, like, understanding and plot. But, back to how I was working on what to pick to put in a short story. I struggled for a really long time actually before I ever got short stories published with writing really, really epic short stories. Because I really liked epic fantasy. It’s really hard to write an epic novel, or an epic sized world in 5000 words. So the first story I ever got published was called Burning Season. It got published at Podcastle. But I remember one of the critiques that I had when I was trying to get it ready was, “This isn’t a short story. This is a novel.” I was like, “Well, I don’t want to write this novel right now. So I’m going to figure out how to make it a short story.” It was basically not figuring out what to put in, but figuring out what to take out. So I just took out as much as I could without losing the meaning. So there was a lot of, all right, well, if I take out this, does this paragraph still makes sense? If I take out this entire scene, and I still get the spirit of what this scene was trying to get across? Basically, I just kept whittling it down and cut until I could condense it into its smallest form while still having the sense of the world and the magic that was required. And the history. So…

[Mary Robinette] Yeah. Fantastic. I think, let’s make a little bit of negative space for our thing of the week.

[CL] Okay. So the thing of the week that I would like to talk about is a book. It’s called Reasons Not to Worry: How to Be Stoic in Chaotic Times by Brigid Delaney. I did not know that I was going to be sharing a sort of pop philosophy book today, but it has been really helpful in reframing not just, like, the world at large, but my writing career or being in the writing industry. Because the idea of stoicism is primarily about letting go of the things you cannot control. By golly, the writing industry is a thing that not a single one of us can control.

[Mary Robinette] What?

[Chuckles]

[CL] So if you are looking into this as a career, whether you’re in it or aspiring to it, you’re going to have to let go of a lot. This could help you do that.

[Mary Robinette] Fantastic. So, as we returned from our negative space, I wanted to kind of switch gears just a little bit and talk about Your Eyes, My Beacon: Being an account of several misadventures and how I found my way home. Even the title of it has a different character.

[Laughter]

[Mary Robinette] Like, The Cook. But one of the things that’s also very interesting about this one from a character point of view is literally the point of view. You’re balancing two character POVs, one of which you give us in first person, and the other you give us in third. Do you remember why you made that choice?

[CL] I think I wanted to make it distinct from… I wanted to make the lighthouse keeper distinct from the sailor, not the pirate. But I think it was because the lighthouse keeper felt more distant, a little more cranky. To me, it was the better way to get across some of that anger. But also, because I often find that two first-person point of use are harder to distinguish. So that was the easier way, for me, as well as I knew I didn’t want to spend a lot of time in the lighthouse keepers point of view. So having these little tiny barks was actually more… It seemed more fitting as a… Like, a section break as opposed to a point of view, so it helped distinguish it structurally as well.

[Mary Robinette] When you said you didn’t want to spend a lot of time in the lighthouse keepers point of view, was that… I mean, I could try to structure this in a different way, but… Why?

[Laughter]

[CL] Because I still think that the story that I wanted to tell was primarily the sailor’s. Yes, it is about their relationship, and yes, the lighthouse keeper also has some changing and growing to do. But, ultimately, it was about the change that the sailor had to make in terms of selfishness and… I don’t know, like… What she was going to give up to be with someone or not give up. That was just more her story. I didn’t… Also, like, there are secrets in the story, and so having too much of the lighthouse keepers point of view would have been harder to obfuscate that without resorting to tricks I don’t know how to do. So…

[Chuckles]

[Mary Robinette] that when you’re looking at something where you are needing to withhold information from the reader, that it is much easier to play fair with them if you stay in third person, because of that distance that you were talking about.

[Erin] I’m thinking about what you just said about relationships and, like, whose perspective we’re in in the relationship, and I’m wondering, like, does that… Do you just tend to find yourself drawn to, like… All of these stories have relationships at their core. Like, one character over the other, and like, that’s always the person you are going in with? Does it ever shift in any way as you learn more about the characters in the story? And, like, whose perspective you want to use?

[CL] I don’t think so. I think I… I think… I have a sense fairly early on of whose story I want to be telling and who has… Again, back to that idea of stakes, who has the most stakes in the relationship or has the most to learn or change from in their convergence. Yeah, so I think I go in pretty well. But it is a little different from my novels when I have more space to have multiple points of view. So, like in The Unbroken and The Faithless, Luca and Terran are both… Like, they have romantic tension but we get both of their perspectives in the novel. That is… It’s very different when I have to show both sides, but it does just offer more nuance. Like, I get to play with the idea, like, with the sailor and the lighthouse keeper. The sailor has all sorts of thoughts about the lighthouse keeper. But we don’t even get to see if all of them are correct. Like, she thinks that she’s snotty or stock up. We don’t get to see her rea… Like, the lighthouse keeper’s reasoning for her snotty and stuck up behavior. Which may or may not actually be her being snotty or stock up. Whereas when you have both points of view, you can almost immediately cut that tension by giving their reasoning. But it creates a different kind of tension. Which is, well, now that we know they both have different opinions of this action, how will they resolve that? So, I think it really just depends on what kind of tension you’re more interested in playing with. Honestly.

[Mary Robinette] Yeah. I think that that’s a really important thing to remind readers, what are you more interested in playing with. Remind our listeners. The… So often we get hung up on oh, this is… What’s going to be the best thing for the market, what’s going to be the best thing for this or that. But, really, it’s about what do you want? As the writer, where do you want to spend your time and energy?

[CL] And, I mean, unless someone has developed this without my knowledge, last time I checked, we cannot read other people’s minds. So sometimes it is more interesting to explore that without… With having a character who only has the same capacities that we do. So…

[Mary Robinette] Yeah.

[Erin] We should develop that. No. We shouldn’t.

[Mary Robinette] No.

[Laughter]

[No, no, no, no, no. Nooo.]

[Erin] Mary Robinette mentioned, like, markets, and it reminded me of something I was thinking about before we started recording, which is that, like, all these stories are in Uncanny. We don’t mean to do it on purpose, but it happened. I’m curious, and also, you worked… You were an editor at Podcastle for many seasons. So I’m wondering now, like, what you think the intersection is between, like, what you’re writing and where it ends up? Like, does knowing… Do you ever write for a specific market? Do you just think it turns out to be a good fit accidentally? I’m curious where that plays into your writing process?

[CL] It’s actually shifted a little bit. Especially now that I do write a fair bit of my short fiction now on commission or invitation. Just because of timing. But I think the reason, for example, that I do have so many short stories in Uncanny has a lot to do with the kind of stories I like to write. I think if I were, like, by percentage, I think most of my short stories are either at Uncanny or Beneath Ceaseless Skies. It’s no… Like, it’s no surprise because those are the ones that I read very often. And, obviously, Podcastle, but I can’t count that because I kind of helped build that taste. So… As an editor. So I know it. But, like with the other two, I think that I’m… I have so many stories in there because that is where I naturally gravitate. It’s… They… Both venues make space for the second world stuff that I like to do. With Uncanny, though, there’s a bit more flexibility for little more of the realistic. I don’t tend to do hard or spacey sci-fi very often. So it’s very often near future, and that tends to go best at Uncanny compared to other science-fiction venues. High character focus, at both venues as well. Oh, we’re on the character podcast, so, yeah. That makes sense.

[Chuckles]

[Mary Robinette] It’s weird. It’s like you write character focused fiction. Interesting. Strange. The first thing that I read of yours was You Perfect, Broken Thing. It’s a story that I keep going back to when people are saying, “Oh, short fiction, you can’t really do much with it.” I’m like, “Excuse me.” Because it’s really, actually… It’s only… It’s less than 4000 words.

[Really?]

[Mary Robinette] Yeah. 3930, according to Uncanny, which has the thing up at the top. But it feels bigger in scope. I think that some of that is how specific you get in this story, in particular with the sensory details that the character notices. Like, we are… It is such a grounded story. We don’t actually go that many places. We go to the gym, we go home, and then we go to the race. How do you think about sensory detail when you’re thinking about character?

[CL] With that story in particular, it’s especially sharp for me because she’s a very embodied character. Most of my characters are, they’re very physical, whether they’re fighters or dancers or athletes. Because that’s just something that I’m very interested in. But it was… That story, I wrote it while I was in some creative writing classes. So I was really, really paying attention to a lot of different things. But one thing that I had rattling around in my head was something from a teacher who said, “Pick something from your job.” At the time, I was a personal trainer. So, pick something from your job, and then just write every single detail about your job. So, that was everything from what do I see at my gym, what do I here at my gym, what are people doing, what are we… Like, what are we drinking, like, what are we eating, like… So that was everything from the sweat to the pre-workout, like, the locker rooms, locker room smells, like there was so much of that. Then, the other thing that I did and I really enjoyed was I did a couple exercises from Ursula K Le Guin’s Steering the Craft. One of my favorite things, so everybody gets like a two-for-one of recommended books for me.

[Mary Robinette] It’s so good.

[CL] There is like one is the write a really long sentence one and one is the write a really choppy kind of crush type paragraph. So if you read the story…

[Oh!]

[CL] You can pick out which ones are… Came from two of her exercises. But they also have high emphasis on sensory detail as well. So…

[Mary Robinette] Those are great, great examples. I know exactly where… What you’re talking about in each. Because we… As our listeners know, we talk about that during the podcasts. I think that that’s actually probably a really good place for us to segue to our formal homework, since were giving you some accidental ones. Like, go read Steering the Craft and do that exercise.

[CL] Do every exercise.

[Mary Robinette] Yes. I think you have some homework for us.

[CL] I do. So I… As you guys can probably tell, I pay a lot of attention to the other instructors and writers who have, like, stuff to share. So this exercise, this next exercise, comes from another writing teacher that I love whose name is Matt Bell. One of his exercises is about… It’s called four scenes about power. The exercise is as follows. You will write for scenes. Whether they’re in a short story, a novel draft, or just like just sort of like triptych quartet thing. One is a scene in which your protagonist does something to someone else, so they act upon them. A scene in which your protagonist does something for someone else. So acting on their behalf. A scene in which your protagonist has something done to them. So they’re acted upon and react to that. Then, finally, a scene in which your protagonist does something with someone or something else. They are acting in collaboration with another character or a group of other characters.

[Mary Robinette] That is a great exercise. Thank you so much for sharing that with us.

[CL] Of course.

[Mary Robinette] This has been Writing Excuses. You’re out of excuses. Now go write.